A couple of spare days between visiting Alto Adige and returning to Barolo during the fall of 2013 led me to the hilly vineyards in the far eastern stretches of Friuli.

It was there that I discovered the remarkable Collio DOC zone and the true potential of the Ribolla gialla grape. Dating back to the 1300s in the micro zone of Oslavia, the part of Collio that dips into the country of Slovenia, Ribolla is one of the region’s most indigenous varieties. Collio’s oldest Ribolla vines, which have sustained life for over 100 years, are located in the Oslavia zone. The roots of the vine prefer the ancient clay soils found here and nearby San Floriano, which reach Collio’s highest altitudes at 280m a.s.l.. The grape, Ribolla gialla, is thin-skinned, does best where there are cool breezes (that prevent rot), and benefits from a little extra hang time for fully ripened phenols, especially if made in the “orange” style.

The Ribolla from Oslavia, or Ribolla di Oslavia, in Italian, is a term that refers to Ribolla gialla made in the orange wine style, using traditional eastern European techniques. The history of this style leads us back to the country of Georgia where it started. It then migrated throughout Eastern Europe, into Slovenia, and naturally to the far eastern stretches of Italy. But it wasn’t so much of a move from Slovenia to Italy more than it has been a shifty border between the two countries. Even today it is nearly impossible to tell where one country stops and the other begins.

Oslavia was a complete battle zone during the World Wars of the last century. The Oslavian ossuary contains nearly 60,000 killed soldiers, over half of which were never identified. Since the wars, its inhabitants (today merely 800) have worked to build the land back up, increase the forestation (it is now more prolific than before the wars) and over the past 35 years, make an intensely exotic, expressive orange version of Ribolla gialla.

As I explained in my previous blog article, “Pinot grigio as ‘Orange Wine’”, this so-called “orange wine” is the result of white grapes that see skin contact before or during fermentation (much like a red wine).

“Orange wine is actually the opposite of rosé wine. Where rosés are made from pressing red grapes quickly and limiting skin contact with the juice (skins give the juice color, tannins, and other phenolic characters), orange wines are made by pressing white grapes and leaving the skins in contact with the juice to give just that: color, phenols (flavors), and sometimes a touch of tannins. Many white grapes can be made this way under certain conditions, not only highly pigmented grape like like Pinot grigio and Ribolla gialla.”

Damijan Podversic and La Castellada introduced me to this particular style back in 2013. As an apprentice of Gravner, the Friulian pioneer of orange wine, Damijan is one of the more extreme producers of Ribolla di Oslavia. He does an extended fermentation and maceration (60-90 days on skins), and ages his Ribolla in large botti (20-30 HL botti (large barrels)).

La Castellada makes a serious version as well with about 14-28 days of fermentation/maceration with skin contact and 4 years aging before bottling (3 in botti and 1 in stainless).

But not all of the producers make orange wine in such an extreme way. It is possible to make an orange style of Ribolla even with only a day or two of skin maceration and a few months of aging in stainless steel. The handfull of producers who make Ribolla di Oslavia in various orange styles are:

Some will argue that orange wines are just a fad, and only appreciated by those bizarre somms and peculiar end-users whose taste buds drift only to esoteric, off-the-wall wines that no one else likes. But making white wines with skin contact is one of the more traditional methods out there, even in modern history.

According to Bastianich & Lynch in their book, Vino Italiano, the light, aromatic wines we associate with Friuli are a newer invention.

“… most Italians were fermenting white wines in the old farmhouse style: throwing their super ripe grapes, skins and all, into open-topped wooden vats, where the fermentations would proceed naturally.”

It wasn’t until the sixties when a handful of producers, including Schiopetto and Livio Felluga decided to preserve the pure flavors of the grapes. And it’s not an easy process. Gently pressing whites and sealing them up (without exposure to oxygen) in temperature-controlled tanks requires money and expensive equipment. These methods created the refreshing and delicate wines—even for Ribolla gialla—that we associate with Friuli today.

In my more recent trip to Collio (June 2015) I was fortunate for the exposure to about 30 different Ribolla gialla wines in all styles.

Some of the best of the leaner, more refreshing styles of Ribolla gialla included the 2014s from Castello di Spessa, Robert Princic (Gradis’ciutta), and Tenuta Borgo Conventi. In the orange style, Draga makes a beautiful, delicate, light salmon-hued version (I don’t think his grapes technically grow in Oslavia), while the more serious Ribolla di Oslavia Rierva from Primosic (I tried the 2009 & 2011) is one of my favorites.

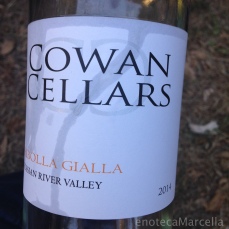

Nowadays the orange style is neither limited to eastern Europe nor the far ends of northeastern Italy. Producers in Australia, South Africa, as well as New York, and California are making them, and with outstanding results. Living in California, I recently became aware of a small, annual, producer-run/producer-attended (except for us sneaky journalists (hehe)) event in Napa called RibollaFest. California producers of Ribolla gialla, and other Friulian varieties in single varietal bottlings or blends, and in various styles, meet to compare their wines and winemaking experiences.

Ribolla gialla in California all started with George Vare, an entrepreneurial vintner who introduced the U.S. to bag-in-a-box wine in the 1970s. After that, he started the Geyser Peak Winery and experiemented with Cal-Ital varieties, establishing Luna Vineyards in 1996. Determined to get Pinot grigio just right, he traveled to Friuli to learn more about it. While there, he met Oslavian producers Gravner and Radikon, and from them, his interest in Ribolla gialla bloomed. George Vare began his own Ribolla gialla vineyard in Napa in 2001 from budwood gifted to him by Gravner. He made wine under his own label (the first vintage was 2004), and sold to a handful of producers including Michael Chiarello of Chiarello, Mark Grassi of Grassi Vineyards, and Dan Petroski of Massican. According to the Matthiassons (who have worked with the Vare vines since they were first planted), the vineyard is quite suitably placed.

“The Vare vineyard is in the cool and foggy southern part of the Napa Valley in the mouth of Dry Creek canyon, right next to the creek. The rocky fluvial soil and cool air drainage of the canyon work perfectly with the Ribolla gialla variety.”

Unfortunately my and George Vares’ paths will never cross, except for only symbolically among his vines; he passed away in April of 2013, about six months before my first visit to Friuli. But as RibollaFest has shown me, there are now quite an arm’s full of California winemakers producing wine not only form the unique George Vare Ribolla gialla vineyard, but also from other little Friulian plantings nearby.

Below is a gallery of just some of the wines I experienced from RibollaFest 2015: all high quality wines and a range of styles to appeal to many palates. Wines you should try and get ahold of include those from Massican, Matthiasson, Forlorn Hope, Arnot-Roberts, Grassi, Cowan and Ryme. I probably missed a few; but I blame that on the abundance of shiners and barrel samples, which is never a bad thing at an event like this…

If you’d like to read more on the subject, here are some interesting articles:

What’s the Big Deal About Orange Wine?

Orange Wines will Never be Mainstream

Napa Vintner George Vare Dies at 76

Attending Ribolla Gialla University, Part 1: Meeting George Vare

2 thoughts on “Ribolla Gialla: Ribolla di Oslavia & George Vare Ribolla”